Where I grew up, there were two categories — kids who played sports and kids who were weird because they did not play sports.

There were kids who were good at math, kids who liked Magic: The Gathering, and kids who didn’t know what they liked yet. But to the greater pool of both parents and kids, this was one group — they were simply viewed as kids who did not throw or catch the ball.

I was good at both the throwing and catching of the ball. My dad was an athlete, and so he raised me as one. I enjoyed it. But the pull toward weird was strong. I was 6 when I first saw the video for Lenny Kravitz’s “Are You Gonna Go My Way” — a chandelier descending upon a long-haired man wearing heels and donning a Gibson Flying V inside some sort of warehouse amphitheater.

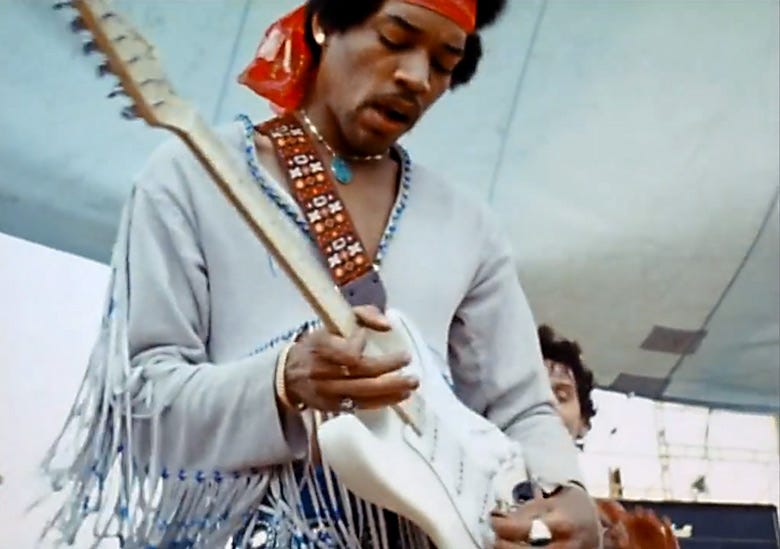

Not long after that, I found Jimi Hendrix and asked my father why he lit his guitar on fire. He pulled the Live at Woodstock double-disc set from the CD tower and told me about the Vietnam War and why Jimi’s guitar sounded tortured and dissonant in his rendition of the National Anthem. I had no interest in kicking or throwing a ball after that day.

It would’ve been better to discover these interests earlier, as making the transition from throwing and kicking a ball to being an indoor kid really confused my friends. As a 5th grader, I could no longer join in on conversations about the game last night or who was going to be MVP, but I could tell you what kind of bass the late, great Cliff Burton played before he died tragically in a bus accident at age 24, and why I felt Metallica would never be the same band after that.

Fortunately, at age 11, I entered middle school, which is where the northern section of my town joins the southern section of my town for the most hormonal two years of young adulthood. Six elementary schools crammed into one building for culture wars, income disparities, and a game of survival of the fittest.

I went through the first seven periods of my first day of middle school sweating it out with extreme anxiety, but I was surviving. There were girls with designer bags and clothes, boys who wore jewelry and had lots of gel in their hair, and then my old friends, who were all a bit crusty and usually had dirt on their knees. I no longer belonged here nor there, so I was floating.

I made it to my last period and sat down in the back of the class. As I peered down to my left, I noticed on the floor a black JanSport backpack with a Black Sabbath patch. Big purple letters. I looked up to find its owner — a kid with big eyes who seemed to inhabit his own world, much like me.

“Do you play guitar?”

There’s no part of me, as an adult, that would be bold enough to jump directly to a question like that with anyone, ever. No introduction. No “Where are you from?” Just the straightforward assumption that if you have a Black Sabbath patch, you must play guitar.

“Yeah.”

Great.

“I play drums. Do you want to hang out after school?”

Again, I look back on this day and wonder if whoever was writing the script for my life was being conscious of word count or episode length, because I have never been this forward about anything. It was as if the sheer desperation in finding my people removed any and all bullshit from the equation.

“Where do you live? I’ll ride my bike,” he said.

After the final bell, Justin rode his BMX bike to my house. He didn’t need to bring his guitar, because along with the 4-piece drum kit my neighbor had given to me when he upgraded, I had a white Squier Stratocaster with a white pickguard, just like Jimi.

We played Rage Against the Machine’s “Guerrilla Radio” and “Bulls on Parade,” and my parents milled about upstairs, unaware of the revelations I was experiencing one floor below them that would inform the entire trajectory of my life after that day.

“My brother plays in a Rage Against the Machine cover band. They have a show today. We should go.”

If a bunch of writers sat around a table scripting this shit, and someone pitched that idea, it would immediately be met with, “I think that’s a little incredulous to all happen in one day.”

I dug my Dyno VFR out of the garage, and we rode across town, eventually guided by the sound of drums and loud guitars serving as our beacon.

The band was set up in the driveway, which was a slab of concrete at the end of loose gravel. A handful of 8-10 kids stood on the gravel watching the band rip through songs from Evil Empire, The Battle of Los Angeles, and the self-titled record. The bassist’s mom filmed on a gigantic camcorder in the corner, smiling ear to ear.

Justin’s brother was the frontman. He sauntered back and forth across the slab of concrete like it was a stage 10 feet above us, delivering every line like he wrote it. There was electricity running through my body.

“We have to do this,” I said to Justin.

“Yeah,” he responded back, without requiring any context.

Over the next 6 years, we spent the majority of our time in bedrooms and in basements, listening to records, learning songs, and making noise. We played backyard shows and VFW halls. It took time, but we both got better.

Eventually, our paths diverged with our tastes. I went toward punk rock and hardcore, and Justin felt the pull toward rap music.

After years apart, we reconnected. I went to visit him in between tours, to the same bedroom at his parents’ place that I’d spent most of my youth in. There wasn’t much “What have you been up to?” It was like he just picked up where we left off.

“Check this out…” he said as he put a vinyl record on his Technics SL-1200 and sampled it into his MPC 1000. I recognized it. It was the song they play in Mars Attacks to kill the aliens. I laughed, but Justin smiled and looked at me like, “Watch this.”

He grabbed only a 6-8 second melodic moment from the record, then chopped up the sample in the MPC. Then he pulled a piano loop from another record and repeated the process. Lastly, he added drums, and my eyes lit up. It was like watching a magic trick.

His brother walked through the door. We exchanged a quick hello, him acknowledging I’m easily a foot taller than the last time he saw me, but wasted barely any time on pleasantries as he dove immediately into rapping over the beat. It was all created in such a way that made you feel like the game was catching it out of thin air before it dissipated. Like you had to move quickly, or the idea would disappear. I was in awe.

In the years that followed, my little band brought Justin and his brother out on various shows and tours. It didn’t make any sense musically, and our fans were mostly puzzled, but I was obsessed with everything they did.

Some more years passed, and Justin’s brother was no longer rapping, but Justin kept making beats. I had a break between tours, and he invited me to visit him at his apartment in Brooklyn. He said he was working with a new rapper. “He’s a chef. Literally. We’re making a tape together.”

I went to his apartment and watched him pull samples from YouTube onto an MPC as a man who introduced himself to me as Action sat at the kitchen table and smoked while waiting patiently for the beat to be finished. We talked a bit. He was really friendly and talked to me about food and his son. Justin paced around the apartment, switching between weed and tea with honey, making small changes to the beat until he was satisfied. Eventually, Action stood up and started rapping.

All this magic. All this beauty. All because 15 years prior I asked a kid with a Black Sabbath patch if he played guitar.

This brought back so many memories!

this was such an enjoyable read. Felt all the same feelings and had all those same thoughts, but just in suburb rhode island, instead of suburb long island. Didn't really find my people until 10-11th grade (04), but once I did - the world opened up in a similar way. None of my musician friends made it further than the VFW halls, but still all of those times have made me who I am now!