I almost cancelled my show last Friday. The reason for nearly cancelling is the same as my reason for not cancelling—my cousin, Scott.

The news of his death came via a family group text that was only used once prior, which seemed to add to the shock. The thread previously contained only one message—four photos from my uncle’s wedding that my dad had sent on October 8th of 2022. Now, just below those photos, was a text from Wai Ming, my cousin’s wife, which read, “Scott passed from cardiac arrest just today. I’m on my way to the hospital.” Scott was 49 years old.

There is no originality or creativity in an untimely death. You’re filled with all the phrases you’ve heard a million times before—cliché words that feel to an outsider as though they lack detail and emotion. As an insider, that’s all you have—“This doesn’t feel real” and “We were just with him.” When I told my father I’d be cancelling my show and on a plane immediately, he hit me with yet another seemingly trite phrase:

“You know he wouldn’t want that.”

I didn’t really want to hear that. I miss out on plenty living on the other side of the country, and I wasn’t comfortable with the potential for my absence to be felt. But when I spoke to my brother on that Tuesday night, he doubled down. “Scott would hate it if you did that.”

There’s a chance Scott saw more of my shows than anyone I know. He lived down in Florida during my peak touring years, and I played there a lot. But he’d use my New York shows as an excuse to see the family and come out to those, too. He was there for every chapter.

Scott’s presence usually meant you could count on seeing other family members, too. He was a self-declared introvert who spent more time asking about everyone else than talking about himself, but he was also a magnet. My family has always been a bit disjointed, geographically speaking and in other ways. If Scott said he was going to be somewhere, suddenly anyone who was on the fence would just cancel their other plans.

In a phone call earlier this week, my dad highlighted this perfectly. He recalled that as my brother and I got to the age where we were dating, and therefore splitting holidays between our family and our girlfriends’ families, the only thing that could change that was Scott. If my parents told either of us that Scott was coming in for Christmas, suddenly we were both willing to endure an argument with our respective partners because we had to be home. It was a non-negotiable.

In case you needed more evidence of that, just a month ago, a large bulk of my family flew into Boston for Scott’s birthday to see the Jets play the Patriots. If you need any testament to the magnetism that my cousin had, look no further. There is no reason to fly to the other side of the country to witness the disappointment of the godforsaken New York Jets in person. Scott was the real reason for us all to be there.

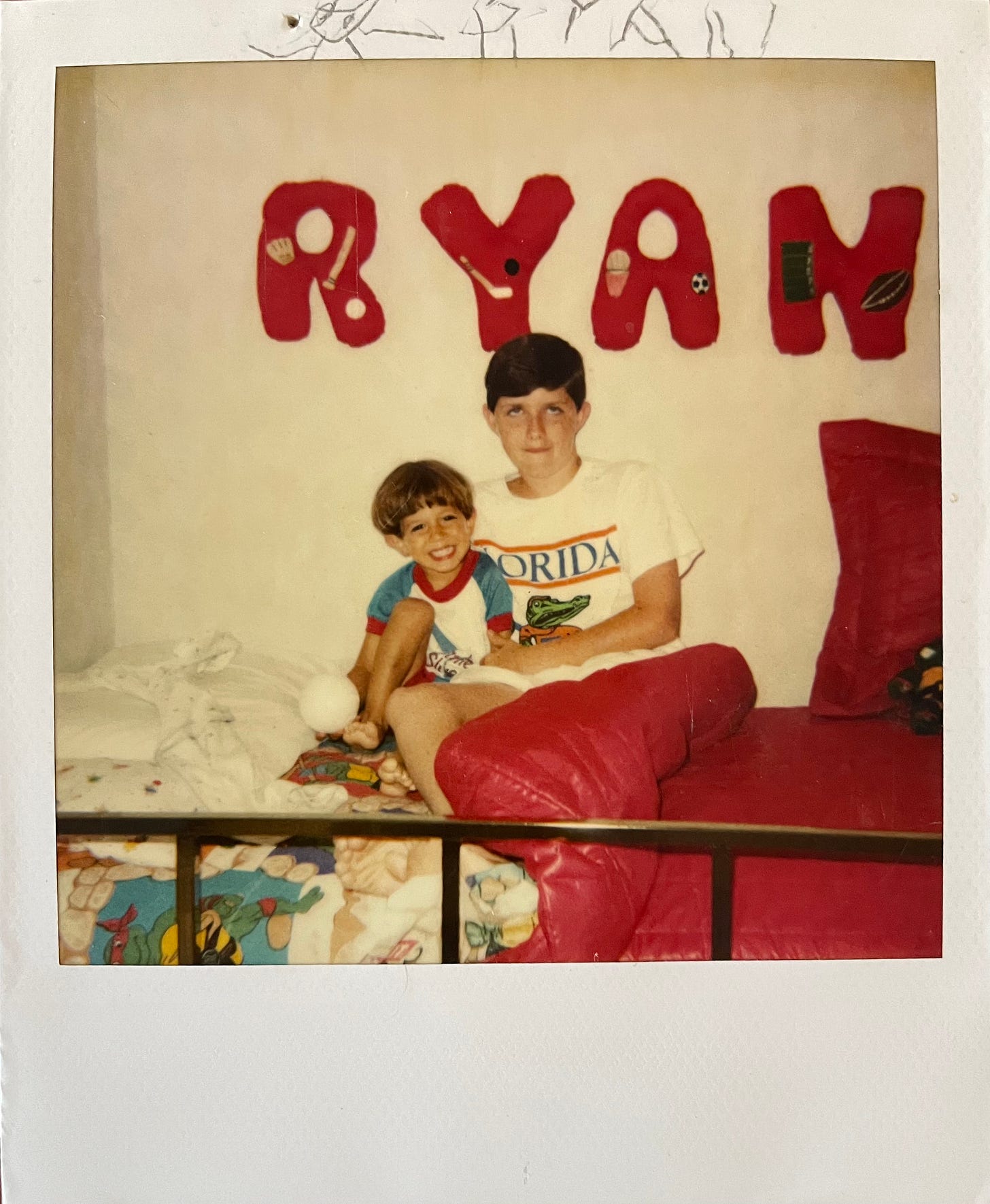

That trend of celebrating over the news that Scott was coming to town started early in my life. He was the closest thing I had to the experience of looking up to an older brother. I remember sitting in my parents’ car outside a CVS parking lot on one of his visits when he told me he’d burn me a CD of some new music he’d been listening to. I didn’t know why he was going to light a perfectly good CD on fire, but I said okay. Eventually, I would grow older, and we’d trade music and movies. But at that very naive age, he was my conduit to anything cool.

Back in April, I shared a piece, “Sea of Limbs,” in which I spoke about a memory I have, which I’m not entirely sure actually happened. It’s an image of complete bliss that I return to from time to time, as it seems void of worry, adult responsibilities, and lives in some sort of dream state that I can’t quite pinpoint. I only know that it’s always been there, in some corner of my mind, revisiting me over the years, without explanation or context. In that memory, I’m playing basketball on a court near a beach in night air that’s humid and moonlit. My cousin, Scott, is there with me. It could’ve happened, as he lived in Florida back then, but I don’t have any idea why this image or memory stuck with me or why it feels both surreal and impactful all at once. The significance is only heightened now that he’s gone. I repress the urge to add to the clichés and question if that image is heaven or if he’s there right now, but I will absolutely cling to the vision for the rest of my life, along with every other memory I have of Scott.

On Friday, I’ll fly back east to be with my family and attend my cousin’s memorial, but I’ve been mourning him since last week. So with that, I’d like to say thank you to everyone who came out on Friday night. To those who called a babysitter for the night so they could be there. To those who’ve been to countless shows, like the woman who flew from North Carolina. To the two of you who flew from Dallas, and to the guys who brought every single vinyl I’ve ever put out and asked me to sign them all. To the guys from Phoenix who showered me in compliments that I can’t even comprehend, to those who drove up from San Diego and from Salt Lake. To those who followed me out here from NY. To everyone I spoke to that night and everyone I didn’t get to. To every one of you, thank you.

Your presence that night meant more than you ever could have known.

This really drives home the lesson that you never know what someone is struggling with because I never would have guessed the grief you were suffering from your performance. I’m so sorry for your loss. I can only imagine he was so proud of you.

What a beautiful tribute! 😢